Africa's emerging megacities offer great opportunities, but will also open new fronts in East-West competition.

New Decade, New Challenges

If the last year has taught us anything, it is that looking too far into the future can be a futile exercise. Decision-makers in politics and business were both caught unawares by the seismic events of the COVID-19 pandemic. Plans were disrupted, budgets were ruined and forecasts utterly undermined.

That said, the world's biggest trends and challenges have withstood the tide of COVID-19. Indeed, in most cases, these have not been derailed by the impact of the pandemic, but instead, look ever more salient. Take the switch to renewables, for example. It was clear that this would be a major policy priority across the developed world over the next decade. All COVID has done is accentuate that trend by hitting oil prices, curbing demand and pushing governments towards splashing out on Green New Deal-type programmes as a way of fuelling recovery.

Sibylline has set out our forecast of the key issues facing the business world over the next decade in our new report "10x10: Ten Themes for the Next Ten Years". We use these select themes to articulate crucial risks and opportunities facing executives up to 2030. Addressing wide-ranging political, economic and social developments, these issues are "COVID-proof": they will influence the commercial environment regardless of dramatic events like those of the last year.

Urbanisation Will be a Defining Feature of Developing Economies

Of our key themes for the next decade, urbanisation and the growth of megacities is among the most prominent. This is due to its interconnectivity with many political, economic and social changes: the growth of China and India, increasing wealth inequality, demographic change and the centrality of digital technology.

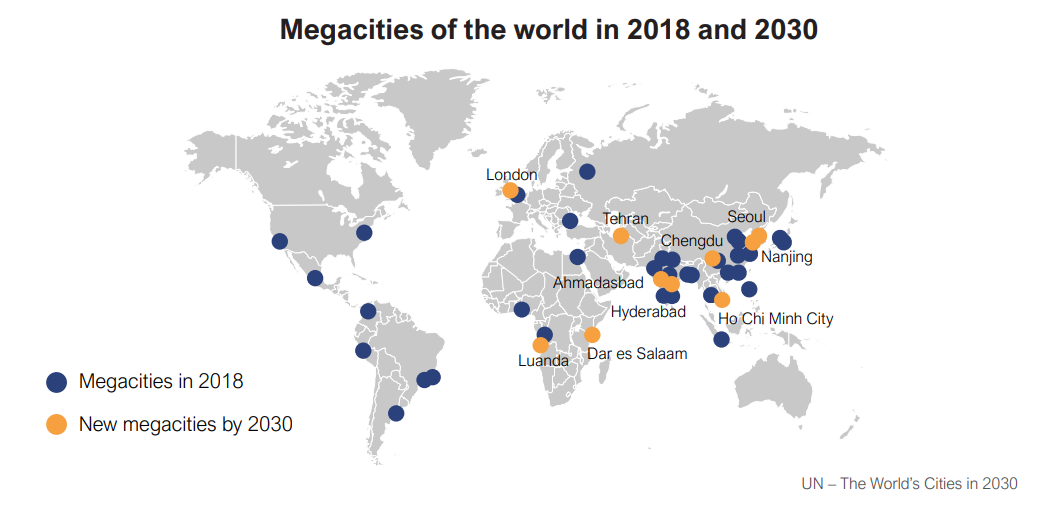

There are currently 33 megacities in the world – conurbations with more than 10 million inhabitants. These are largely concentrated in South and East Asia, with five in South America and two in the US. By 2030 this figure will have risen by nearly 25% to 43. All but one of the new megacities will be in Asia and Africa, signalling the rate of those continents' development. Notably, there will be no new megacities in the Americas and only one – London – in Europe, which is unlikely to change significantly, given it already sits amid a densely populated commuter belt.

The new megacities of Asia and Africa are therefore worth some consideration. These include predictable candidates in India and China, such as Hyderabad and Nanjing. However, there are also others whose growth symbolises the dramatic development of their host nations over the last three decades, such as Seoul and Ho Chi Minh City.

Meanwhile, others will come as more of a surprise; how many board-level executives in London and New York would have put Tehran among the world's next megacities? Moreover, what does that shift say about demographic and social changes underway in Iran? Is the current system of government capable of containing the intellectual and economic forces unleashed by over ten million people living in close proximity?

African Megacities Set to Double

It is in Africa, however, where urbanisation presents both the greatest challenges and opportunities. The continent already hosts three megacities - Cairo, Lagos and Kinshasa, and by the end of the decade, it will have two more in Luanda and Dar es Salaam. Even beyond these metropolises, there are several other major conurbations that are megacities in all but name. Nairobi may technically have a population of around 4.5 million, but its greater urban area contains over 9.3 million and counting, no doubt passing the 10 million mark well before 2030. Similarly, the population of Johannesburg's urban area has been over 8 million since at least 2019.

Not only does Africa have some of the leading candidates for the next generation of megacities, but those currently in that category are continuing to grow at a frightening pace. Kinshasa, capital of the Democratic Republic of Congo, was the world's fifth fastest-growing city by population from 2000-2020 (just behind Beijing), while Cairo and Lagos were seventh and eighth respectively. Meanwhile, Luanda, Angola's capital, had the second-highest growth rate globally in percentage terms over this period, exceeding even the likes of Delhi, Dhaka, Beijing and Shanghai.

These dramatic changes present challenges of equal proportions. Ever since Britain became the world's first urban economy around the 1840s, governments have struggled with the challenges of transport, sanitation, housing and public health. Given the speed of Africa's urbanisation and the relative poverty of its cities' new arrivals, this analogy may be more apt than one might expect. The slums of Kinshasa and Nairobi, for example, are vast and growing, while an estimated 85 people arrive to live in Lagos every hour, presenting a colossal challenge for planners and administrators.

The Challenge of Urbanisation Also Presents Major Opportunities

That said, for business, these epochal shifts in the fundamentals of African society present significant opportunities. The continent's governments have benefitted from leading global growth rates in recent years are ready to invest in the infrastructure their growing cities need. The construction and engineering sectors will boom across the continent, with foreign operators set to benefit as well. However, western firms in the industry will need to position themselves intelligently to out-compete Chinese competitors. The latter have spent much of the last 20 years establishing track records delivering major infrastructure projects across Africa with Beijing's backing. When Dar es Salaam looks to upgrade its transport network or Luanda wants to emulate Lagos' mass transit rail system (currently under construction), Chinese firms will be their first port of call. Western business will need to push their own politicians hard to leverage diplomatic ties to make themselves competitive; something that the Turkish government has enjoyed quiet, but growing, success in over recent years.

If engineering and construction looks to be a difficult field to break into, western businesses may fare better in tech and e-commerce. Africa has a track record of technological leapfrogging; just take telephone and online banking for example, which was taken up with an enthusiasm on the continent that made European counterparts appear Luddites by comparison. Just as cities in the west have provided ample opportunity for tech startups to provide niche, but highly profitable services, so Africa's urban centres will create a growing market to exploit. The continent also has some of the youngest populations in the world who form ready markets for innovative tech platforms; Nigeria's average age is only 18, and will still be below 20 by 2030, while Kenya's median age is 20. Mobile infrastructure is one of the continent's strengths and it already has a huge informal sector with a massive potential workforce on which service-focused, app-based platforms could build. Moreover, this has not been lost on African entrepreneurs, who have formed thriving regional tech hubs in Nairobi, Lagos and Cairo that are ripe for targeted investment. Savvy venture capitalists in London and New York could do far worse than looking to bet on Nigeria's next Uber or a Kenyan Stripe.

Healthcare provision within Africa's megacities and other rapidly growing conurbations will also need to evolve dramatically to keep pace with demand. Regional governments are aware of the need to spend more, to safeguard both their citizens and their own prospects of in staying in power. Some cities will enjoy a head start in this respect, such as Nairobi, already East Africa's medical hub, but others, like Kinshasa, are building from a low base. Healthcare will be another key focus of east-west competition, especially in the aftermath of the pandemic. China and Russia's ready provision of COVID vaccines ahead of western competitors will earn lasting sympathy in much of Africa unless Europe and the US up their game. American healthcare providers and the European pharmaceutical industry can both benefit from soaring demand in Africa's major cities over the next decade. Again, however, this will need diplomatic engagement and trade policy to be appropriately aligned with commercial opportunities.

Executives can be assured that the next ten years will be rife with challenges, not least bouncing back from COVID-19 and winning the battle against climate change. However, opportunities in new markets abound, with urbanisation being but one of several key drivers of growth. In order to realise these prospects, engage intelligently with governments, and advocate commercially sound policymaking, business leaders need to be better informed than ever.