Marketing is embedded in the lives of anyone who has a pocket full of spare change, but have we always been susceptible to marketing strategies, sales ploys and trade games? Starting with day one, John Harrison, Managing Partner at BBH London, speak to CEO Today about the history and evolution of marketing, the process that made us buy things yesterday, still does to this day, and will forever ‘con’ us into spending more.

Much to my mum’s chagrin, Marketing was invented 6,000 years ago by Satan. Whatsmore, he did it whilst being disguised as a snake.

This is the first recorded incidence of someone doing what Marketing fundamentally exists to do. To convince someone that your option is better than all the other options they have available to them.

Credit where credit’s due, in this particular case Satan used a very powerful emotional brand positioning for his apples. He positioned them as a way of making his target audience “like God”. If that isn’t taking them up to the top of Maslow's hierarchy of needs then I don’t know what is. It makes my attempts to position a well known mobile phone network as “social glue” seem positively amateurish.

Of course, this first use of Marketing didn’t work out too well for the world’s first consumer - Eve. Or Adam. Or the entire human race to be honest. But as I’m sure you can appreciate, there are usually teething problems with all new disciplines.

If Marketing really is about convincing someone that your brand is better than all the other options they have available to them, then it really comes into its own when supply outstrips demand (though of course, Marketing can also play a crucial role in making demand outstrip supply - the current waiting time for a Tesla is about one year after you’ve paid your deposit).

The annoying truth however for most businesses and brands is that consumers are utterly overwhelmed by choice[1]. There’s a painfully illuminating scene in the 2006 film Borat, where Sacha Baron Cohen’s alter ego spends what feels like an eternity going up and down the same supermarket aisle, pointing to each of the different items for sale, asking “And what is this?”. Each and every time Borat asks the question, the remarkably stoic supermarket manager gives the same one-word reply. “Cheese”. It’s enough to make even the most enthusiastic Dairy Marketing Director cry out “Who on earth needs that many different types of cheese?”

Now the chances are that your business probably isn’t competing against 87 other brands of cheese. But I’d be willing to wager a whole wheel of Edam that one of the questions that keeps you awake at night is “what will make the consumer choose us over the competition?”

So if Marketing exists to directly answer this question, then why is it frequently treated as a peripheral function Why are Marketing budgets typically the first thing to get cut in financially turbulent times? Why do less than 1% of Fortune 1000 companies have a CMO on their board[2]? Why are there twice as many FTSE 100 CEOs with a finance background as there are with a marketing background[3]? Why do CMOs have the shortest average tenure among all C-suite roles[4]?

Alas, I fear that Marketers are at least partly responsible. Many have an incurable tendency to overcomplicate things - not least what the role of Marketing actually is. They have more acronyms than the FBI and NASA combined. They can forget the motivations of their internal audience and talk to their CEOs about fluffy, intangible things such as ‘brand pyramids’ and ‘affinity’. In truth, it can all feel a bit, well, peripheral.

However, the best Marketers are able to demonstrate the fundamental role that their function plays in driving business success. They help build strong brands that your target consumers will choose (and continue to choose) over all the other seemingly equal choices available.

So it’s clear that convincing someone to choose your brand over all the other options they have available to them is what Marketing exists to do. How it does this is by understanding which of the available brand levers should be pulled in order to strongly influence consumer behavior. It used to be accepted that there were four such brand levers, commonly known as ‘the 4 P’s of Marketing’. Some Marketers will try tell you that there are now 7 Ps - remember my point about having an incurable tendency to overcomplicate things?

Price: What is the maximum possible price that the optimal number of people are willing to pay? Strong brands deliver between 6-13% price premium and reduce price elasticity[5].

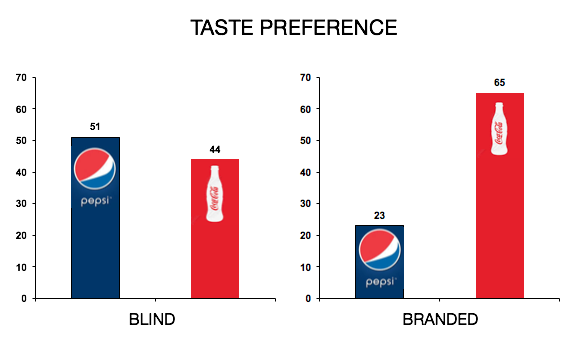

Product: The pace of change means that product advantages that provide a much coveted ‘Unique Selling Point’ are becoming harder to find, and even harder to keep. Perceived product advantages are still something strong brands should strive for however, as seen in the oft quoted Coke v Pepsi blind taste test[6]. The strength of the Coke brand physically improves the product experience.

Place: As Byron Sharp has made clear in his book ‘How Brands Grow’, you can have all the mental availability in the world, but it won’t do you any good if your brand isn’t physically in the right place at the right time for people to buy it.

Promotion: The application of creativity in communications can provide an unfair competitive advantage. As shown by the fact that creatively awarded campaigns are 11 times more efficient at driving share growth[7].

The arsenal of channels, tactics, tools and technologies that Marketers are able to deploy is constantly changing, and that pace of that change will only continue to speed up. However, for over 6,000 years the fundamental role of Marketing has remained the same - to convince someone that your option is better than all the other options they have available to them.

Thank Satan for that.